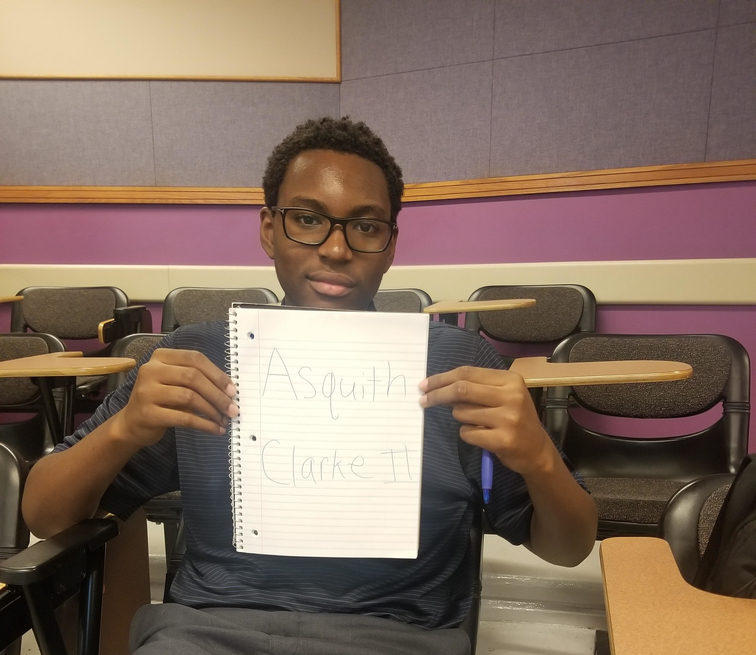

Asquith Clarke II (C/O 2021) loves his name and has no problem correcting you if you get it wrong—especially if you forget the II. That’s the most important part. It lets you know that Asquith is his father’s son.

Asquith Clarke II is the name he put on a successful application to GripTape last year, where he converted his love of video games into a quest to learn code. It’s the name he put on his winning applications to Dickinson, St. Olaf, Bard, and Macalester Colleges, where he hopes to pursue a degree in Africana Studies. It’s the name he used for the Oberlin Fly-In program where he learned that Africana Studies exists. And it’s the name he put down when he first joined TeenSHARP his junior year of high school.

Since then, Asquith has emerged as one of the most involved, committed, and driven scholars in the TeenSHARP program—constantly evolving, in honor of his own limitless potential and the legacy of his father. “He was a really good man,” Asquith says of his dad, “and he only wanted the best for me.”

Mr. Clarke worked 18 years for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) while raising raised Asquith, his sister, and her two young children in a two-bedroom Bed-Stuy apartment. Growing up, Asquith shared a room and a bed with his father—so he was there in the early mornings when Mr. Clarke would rise for work, first pressing an outfit for Asquith and then taking him to school. Mr. Clarke was the kind of dad who cared more about an honest effort than a grade, but he took his son’s education very seriously.

“My dad and I had a shared goal for my future,” Asquith says, “that I would do better.”

When Mr. Clarke set off to the subway station in the morning, Asquith went to school: a disproportionately under-resourced academy in Brooklyn where there was constant fighting, broken vending machines, metal detectors, and bars on the windows. It was a violent environment that felt more like a jail than a place to learn, Asquith says—the product of systemic, racist oppression, and students lashing out at rules that didn’t serve them. The days were long, stretching from 7 a.m. to after 6 p.m. since Asquith was on the swim team.

Mr. Clarke was clocking long days, too, as a token booth clerk in the subway station, where he sold Metrocards and helped passengers with directions to their destinations. Even when he wasn’t at work, Mr. Clark was a helper, Asquith says. He once helped a person in a wheelchair get into their winter coat at a cold bus stop. He paid for someone’s pizza when he saw they were short on cash. And while young Asquith preferred to lock the bedroom door for peace and quiet after a grueling school day, Mr. Clarke—also exhausted—left it open so his grandchildren felt free and welcomed to visit.

When Asquith was in middle school, Mr. Clarke passed the exam for a promotion and become a supervisor at work. Now he’d be on his feet all day—sometimes the first to respond to incidents on the tracks, like when there was a “man under.” That’s when things got hard, Asquith says, even with a pay raise. His father’s already-long shifts became interminable, and he brought work home at night. Some mornings, Asquith would have to wake him up because he was so tired, or help Mr. Clarke get shoes on his swollen feet. Regardless, he still pressed clothes for Asquith and drove him to school.

“He always took the time to show me that love,” Asquith says. Asquith was just a freshman in high school, a year or so later, when his father passed from a fatal heart attack.

Today Asquith has a room of his own in New Jersey, where he lives with his mother, and attends a better-resourced school than he did in Bed-Stuy. (There, he’s succeeding in Honors and Advanced Placement courses.) He presses his own clothes, and often wears a blazer and a button-down—even on Zoom. He’s the embodiment of the words “young leader and scholar.”

He says that wouldn’t be possible without TeenSHARP. The organization has shaped his “mind, body, and soul,” he says. “I really feel TeenSHARP is a blessing from God and my late father.”

In writing the story of his own life, Asquith has chosen a narrative of resilience, reinvention, and authentic self-actualization—even in the face of extraordinary hardship.

When TeenSHARP Co-Founder Mrs. Tatiana learned that school officials didn’t properly explain Honors or Advanced Placement courses to Asquith, she was on the phone with his guidance counselor shortly after, advocating for his inclusion. “She spoke up for me as if I was her own child,” Asquith says. “That really stuck with me.” When he struggled in math class, it was Ms. Jen—a tutor from TeenSHARP partner Education United—and Mrs. Tatiana who sent letters back and forth with the principal and teacher, to ensure Asquith had the support he needed. And when COVID-19 forced a move to remote learning, it was Ms. Maija who brought some structure and calm to Asquith’s daily routine through our Zoom-based TeenSHARP program, Orchestrate, that runs the length of the school day. They worked on school assignments and discussed time management, but Ms. Maija also taught Asquith deep breathing and mindfulness exercises.

At some points, Asquith was the only student enrolled in Orchestrate—but he still showed up. “It saved my life,” Asquith said. “And I don’t think I would have been able to pass without it.”

Asquith persevered through the pandemic every we he knew how, even purchasing new glasses when he began to develop migraines from long stints on Zoom. Along the way TeenSHARP was there, in a year when many young people took major drops in their grades that precluded them from success they were otherwise working hard for.

“We would not let that happen with Asquith,” says TeenSHARP Co-Founder Atnre Alleyne. “Asquith worked extremely hard, and we were all relentless, to keep his options open.” Now Asquith has 11 colleges to choose from.

Here’s what Asquith wrote in his portfolio submission to prospective colleges this year:

With TeenSHARP’s continuous support I was able to learn technological resilience, adapt through these technical problems and stay engaged despite these undesirable effects this pandemic has caused. I decided to create study groups for almost all my classes to facilitate engagement with collaborative student-led study sessions and google chat. And when a problem was completely out of my control and unfair, TeenSHARP empowered me to advocate for positive social changes in my school regarding equity, inclusivity, and social justice

TeenSHARP also opened Asquith’s mind to exploring his cultural identity and Black excellence; matters of social justice; and how he can use his voice as a force for meaningful change in this world. His advocacy is just as creative as Asquith himself. On the one hand, he’s part of a group calling for a more diverse and inclusive curriculum at his school. On the other hand, he designed a video game called “The Hoodie” to confront the dominant, single narrative of Black people and other marginalized identities in America. “People need more than one story,” he says.

In writing the story of his own life, Asquith has chosen a narrative of resilience, reinvention, and authentic self-actualization—even in the face of extraordinary hardship. His world changed on the day his father passed, beginning a period of transition from one school to the next, one household to the next, and one reality to the next. Yet Asquith was determined to fulfill the dream he and his father shared.

“It’s terrible that my father is gone,” Asquith says. “But I know my dad is resting now, and he isn’t suffering anymore. People said I was resilient after his death. I was just motivated to do my best.” As for that age-old question, “What’s in a name?”, Asquith would say there’s a lot. “It is very amazing to share a name with my father,” he says, “and it makes me very proud.”

What’s in a name?

What’s in a name?